Finding Teranga

"If you had the opportunity to sit down for a meal with any notable celebrity, dead or alive, who would it be?" For years, this question has been easy for me: Anthony Bourdain! Bourdain shaped my approach to travel and food like no one else. Enjoying the small things, the conversations, the quirks, the mishaps, and documenting them all. Parts Unknown is, for me, some of the most entertaining and inspiring content out there. I couldn't point to a single episode that I prefer, but a few stand out, one of which was his trip to Senegal. The conversation that marked me the most was during a meal with Youssou N'Dour, a Senegalese musician who expressed the importance of teranga in Senegalese culture:

"The most important value is what we call 'Teranga.' The more you share, the more your bowl will be plentiful."

My grandfather worked as a sailor between West Africa and Europe, bringing African produce to the European public. My dad, uncles, and aunts grew up between the ports of Abidjan and Dakar for most of their upbringing. Having lived in Senegal, my grandparents were no strangers to the concept of teranga, speaking so highly of their experience living there. My uncle would often tell stories of leaving the house for days to play football with people around town, always being fed, housed, and taken care of by complete strangers. Teranga in action.

Late last year, Charlotte and I traveled to Senegal with no real plans, just wanting to find teranga and experience it for ourselves.

Senegal is the westernmost country of the African continent, benefiting from nearly 700km of coastline. The country is well known for its culture of fishing, which is reflected in its cuisine. The beaches off cities like Dakar, Saint-Louis, and Cap Skirring act as marinas and shipyards for local fishermen. Colorful pirogues dominate these shores—traditional wooden boats painted in vibrant blues, reds, and yellows, with each fishing family designing and decorating its own vessel. From dawn till dusk, they come and go, pushed along wooden logs that crew members carefully place on the sand. It's quite the spectacle.

To really experience this culture, we spent three days camping on the Sine Saloum River delta, about five hours by taxi brousse (local shared taxi) south of Dakar. We met with a local guide we had found on Instagram and set off from the port of Dangane.

The first stop on our journey was the small village of Fambine where we were invited to tea with the chef du village and his wives. We discussed his upbringing, his fisherman career before being elected, the election process amongst other things. He had met his wives in neighboring villages, as had most other men in the village; men would stay, while women would travel to their husbands' villages. The men would leave for weeks to fish and the women would take of family at home. He spoke of a simple life of community in a calm, wise manner, seemingly aligned with the idea of teranga we had heard so much about.

That evening we set up camp on a peaceful riverbank, listening to Senegalese music as we braced ourselves for a sweaty, mosquito-infested night, counting the hours until dawn would finally chase the bugs away.

Our pirogue set off in the early morning, heading toward the open waters of the Atlantic. The wind picked up and our worries about mosquitoes finally subsided. En route to our next camping spot outside Dinouar, our guide started preparing lunch—a meal he made every day that I simply have to mention.

Thieboudienne (or Thiep) is the national dish of Senegal. You can find it pretty much anywhere, from the markets in Dakar to the smaller household eateries in the middle of the brousse. The dish starts with frying a grouper-like fish in oil, then removing it to cook carrots, cassava, sweet potato, and cabbage. Once the vegetables are softened, they're removed to make way for rice that's cooked in the remaining flavored oil with water. I may not do it justice, but it's honestly one of my favorite dishes and fondest memories of the trip.

We camped on a west-facing beach to watch what was one of many spectacular sunsets of the trip.

Our final destination was Djifer, a famous fishing village in the delta known for its fish trade and serving as the first port into the delta from the Atlantic. Djifer is where most young people aspire to go to find work, as fishing is generally the highest-paying job locally.

The place is bustling and verging on overstimulating—sea snails sold on the sand, drying fish so pungent it stings your eyes, huge pirogues flying in with 15 to 20 people aboard, and quite a few stares as we clearly stood out. It was hard to take the camera out here.

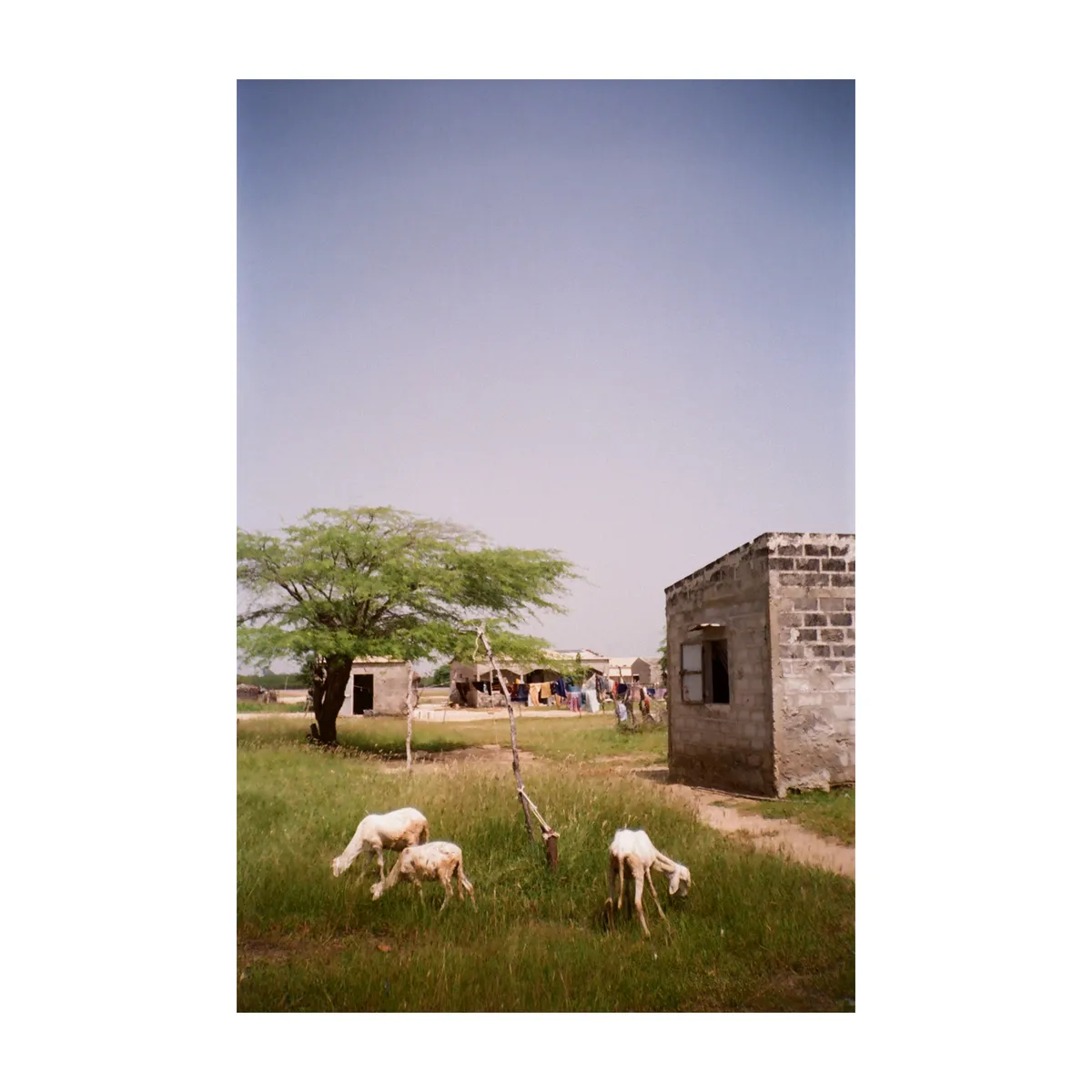

Behind the chaos lies a reality that Senegal faces across the country. Like many larger port towns, Djifer serves as a main departure point for boats heading toward Europe. Nearly every person aged 18 to 35 we met throughout our trip had braved the two to three week long journey at least once—a shocking but understandable statistic. With rising temperatures, fish stocks are diminishing closer to shore, forcing fishermen to travel further into the Atlantic. Climate change is also affecting people inland, with temperatures hitting 45°C and poorly insulated housing offering little relief.

Our journey back to Dangane felt bittersweet. We had experienced teranga in action as we had hoped—pure hospitality and community. But we were also shown that teranga alone was not necessarily enough for the people of the delta, who more than ever sought better lives elsewhere.